Axminster and the London butter trade, 1780 to 1840

This section of text draws heavily on Charles Vancouver’s highly informative 1808 report entitled ‘General View of the Agriculture of the County of Devon; with observations on the means of its improvement’, which formed part of a much larger series of reports produced for, and published by, the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement. This book can be found on-line via the archive.org website, or in an edition published in 1967 by David & Charles Reprints of Newton Abbot. A copy of this 1967 re-print is held in Axminster library.

This section of text draws heavily on Charles Vancouver’s highly informative 1808 report entitled ‘General View of the Agriculture of the County of Devon; with observations on the means of its improvement’, which formed part of a much larger series of reports produced for, and published by, the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement. This book can be found on-line via the archive.org website, or in an edition published in 1967 by David & Charles Reprints of Newton Abbot. A copy of this 1967 re-print is held in Axminster library.

What Vancouver provides is an educated overview, not just of farming in Devon just after the turn of the century, at a time when foreign trade was being severely disrupted by the Napoleonic wars, but also of the social and economic conditions which were influencing the investment and farm management decisions of landlords and tenants alike. This was a time when very few small-to-medium owner-occupier farmers were to be found, certainly in East Devon.

His report provides a significant amount of detail about grassland management and the economics of dairying in East Devon, and what he writes is very much in tune with what other contemporary writers reported.

After commenting on the high quality of the grazing he identifies dairying as the main farming activity. Most of the butter (which was the main product of the dairies) was sent to London. It was made from fresh cream, and not from clotted or scalded cream, which had by then been “… entirely abandoned in all the large dairies, as well as in most others that supply the larger markets in the country”.

The local dairies of the time almost all milked North Devon cows, which nowadays would be considered an exclusively beef breed. The explanation appears to lie in the “… great demand and high price given for the calves of this breed for raising …”.

After leaving milk to stand for 48 hours in cooled vessels the butter making process began. “In summer, it is churned every day, and cheese is made of the skimmed milk. In the autumn, this [is done] … every other day; and in winter, sometimes, but not always, twice a week”. Butter made in this way was considered to taste fresh, with good keeping qualities, particularly when compared with butter made from clotted cream, which was often found to taste smoky. The butter was then salted in small barrels (firkins) weighing 48lbs. The London butter merchants would then do their best to wash any excess salt out of the butter after it arrived in London, so that they could sell it at a higher price.

With the exception of a type known as ‘Membury’, the local cheese, which was made as a by-product of butter-making, was considered to be “… of an inferior quality, and generally destined for domestic use”. Membury cheese was made from full milk, and mostly came from Membury and the Yarcombe valley.

Vancouver reports that although some dairies were managed by the farmer and his family, most were rented out to specialist cow keepers or dairy men. He notes that the cost of renting a dairy varied between 9 guineas (a guinea being worth £1 1s) and £10 per cow, with the farmer providing about 2½ acres of pasture and meadow ground to supply “… the summer food and winter foddering of each cow, during the 42 weeks she is supposed to be in milk. The remainder of the time the cows are fed with straw in the farm-yards, and in day-time range at large over the coarse grounds and commons”.

A cow with her second or third calf at heel was reported to be worth about 13 guineas. When her milking life was finished, she would be fattened for sale, providing further justification for the popularity of Devon cows in dairies, despite the availability of more specialised dairy breeds, such as the Shorthorn.

Vancouver sets down in some detail the typical costs and returns of a 20-cow dairy, which was a typical size of enterprise. It was usual to keep a bull on a dairy of this size, at the same cost and rent as a cow.

As can be seen from the budget below, for every cow that they kept, dairymen generally bought one pig at the beginning of each season at £1 each, which they fed on waste milk and whey, and sold at the end of the season, when fat.

| Typical budget for a dairy of 20 cows and one bull | |||

|

£ |

s |

d |

|

| Annual income: | |||

| Sale value of butter (1lb per cow per day for the first 20 weeks, plus ½lb per cow per day for about 20 weeks, making 206lb per cow or 4,120lb in total at 1s per lb) |

206 |

0 |

0 |

| Sale value of cheese (1¼ cwt per cow, making 25 cwt at 25s per cwt) |

31 |

5 |

0 |

| Sale value of 20 calves (i.e. one calf per cow per season) at 28s each |

28 |

0 |

0 |

| Profit from feeding whey etc to 20 pigs at 25s each |

25 |

0 |

0 |

| Total cash income |

290 |

5 |

0 |

| Annual costs: | |||

| Rent for 52½ acres of pasture and meadow land (38s per acre) |

99 |

10 |

0 |

| Parochial payments (10% of net rent) |

9 |

9 |

0 |

|

Tithes (2/6d per acre) |

6 |

11 |

3 |

| Wages, board and lodging of a dairy maid for a year |

16 |

0 |

0 |

| Wages of a man for foddering, cleaning cow sheds etc (20 weeks at 8s) |

9 |

0 |

0 |

| Cost of hay making (17½ acres at 8s per acre) |

7 |

0 |

0 |

| Cost of fuel for use in the dairy (8s per cow) |

8 |

0 |

0 |

| Annual wear and tear of dairy utensils |

4 |

0 |

0 |

| Annual depreciation (see below) in the value of the dairy (10s per cow or bull) |

10 |

10 |

0 |

| Cost of capital (£350) at 5% |

17 |

10 |

0 |

| Allowance for contingencies (5% on gross value of produce) |

14 |

10 |

0 |

| Total costs |

202 |

0 |

3 |

| Net profit to the cow keeper and his family |

88 |

4 |

9 |

The depreciation charge was there to provide a fund with which to replace cows as they come to the end of their useful life. In a herd of 20 cows, 3 or 4 cows might need to be replaced each year.

Vancouver also comments that “… one dairy-maid would not be able to perform more than half the work required for a dairy of 20 cows. The remainder is therefore supposed to be supplied by parish apprentices, and the farmer’s wife and daughters, all of whom are seldom without the necessary qualifications for such employments; being, with very few exceptions, careful, neat, tidy and industrious.”

Further corroboration of the general picture of dairying and butter making which is painted by Vancouver can be obtained from other sources, which confirm that most butter was covered by fixed price agreements almost all the way from udder to table – between farmers and dairymen, dairymen and local merchants, and local merchants and London cheesemongers. One visitor to Axminster in the 1780s was reported as being unable to obtain any butter, because all the larger dairies were under contract to London dealers.

During this pre-railway period all freight went by road or sea, and butter from East Devon and West Dorset was one of the main cargoes that the road hauliers carried. The normal charge for transporting 1 cwt of butter to London by fast road transport (5-6 days) was 9s from Exeter, or 8s from anywhere between Honiton and Dorchester (i.e. just under 1d per lb). Most other goods paid a higher unit carriage charge, reflecting the importance of butter to the overall economics of road haulage, and its relatively high density, and the robustness of the wooden firkins when packed alongside other items.

Several sources use Cambridgeshire butter as the benchmark for price-setting in London. Cambridgeshire butter was salted enough to keep for ten days or a fortnight, and in 1795 was sold in London for 3d per lb less than the very limited volumes of fresh butter, and 2d more that heavily salted Irish butter. Butter from Dorset (and East Devon) ranked just below Cambridgeshire butter in desirability and price terms, because it was more heavily salted than butter from Cambridgeshire, but much less so than that from Ireland.

Although comparable coastal shipping records have not been found, it is thought likely that much of the butter from the Exeter area was more heavily salted than Axminster butter, and sent to London by sea, while the closer to London (and the further from the coast) a farm was, the more likely its butter was to be carried by road.

James Davidson, the chronicler of all things pertaining to Axminster, included in his papers as stored in the Devon Heritage Centre a list of ‘Occupiers of land that are titheable to the vicar, 1828. Number of cows kept’. This is followed in his notebook by an equivalent list of cows kept on farms which were exempt from tithes.

What is not stated is precisely how the information on the numbers of animals being kept was collected. However the large number of farmers with 20 cows, and the absence of any with 17 to 19 or 21 to 25, is consistent with Vancouver’s findings as reported above.

The total number of cows in Axminster parish came to 919 (776 on titheable land, and 143 on exempt land), with most of them being kept by farmers with 10 or more cows. These larger herds accounted for 77% of those on titheable land, and 85% of those on exempt land.

Some of these cows were kept on remote farms (e.g. Shapwick), but there is no realistic way of reliably separating these out from the main body of data, because the farms are only named in a minority of cases.

In descending order of scale, the numbers are as follows. Farms marked with an asterisk (*) were exempt from tithes.

Return to Occupations

|

No of cows |

Proprietors |

Sub-total |

| 40 | George Davey Ewens, John White. | 80 |

| 32 | Henry Fowler. | 32 |

| 26 | John Seaward. | 26 |

| 25 | Lawrence Mellar. | 25 |

| 20 | Thomas Barns, John Bradfield, James Gill (Slymlakes*), John Harvey (Woodhouse), Francis Harvey, James Hoare, Robert Mullins, William Mullins (Lodge*), George Phippen, Mr Row (Balls*), Samuel Swain, James White (Millbrook / Sector*), William Whitemoor. | 260 |

| 16 | Thomas Baslyan, James Denning, Thomas Gould (Yetlands), John Welch. | 64 |

| 15 | James Chick, William Newbery (probably Symondsdown), James Swain (Abbey). | 45 |

| 14 | James French, Benjamin Hodder, James Pavy, James Rendall, George Slyfield. | 70 |

| 12 | Henry Bussell, Jack Hill, Mr Wakley (Weycroft*). | 36 |

| 10 | Bernard Cox, Richard Denning (Furzley), Richard Denning (Tolshays), Richard Denning (Park), William Henley (Horslears*), William Norman (Raymonds Hill*), Samuel Stoodley, John White (Shapwick*). | 80 |

| < 10 | Other small herds on titheable land. | 180 |

| < 10 | Other small herds on exempt land. | 21 |

| Total | 919 |

It is not possible to say whether there were three separate cow keepers called Richard Denning, each with 10 cows; or one with 30 cows spread over three farms, though the latter seems more likely. The same general point applies to James and John White.

By way of context, there are about 40 named cow keepers in the table above (the precise number depending on the answer to the question posed in the previous paragraph), while the 1831 census counted 99 farmers in Axminster parish in total, of whom 67 employed non-family labour and 32 did not. By the time allowance has been made for all of the smaller cow keepers, it is clear that most Axminster farms had a dairy in the late 1820s.

Flax growing in East Devon in the late 18th century

Flax (also known as hemp) is now cultivated for its seeds (also now known as linseed), which are rich in oil and used as livestock feed and in some health foods. In earlier times it was grown for its fibre, which was extracted via a process known as ‘retting’, and spun into fibre. It was particularly important around Chard, Crewkerne and Bridport, where it was processed into linen, rope, nets and sail cloth. It was also used in the backing of some of the carpets made at Axminster.

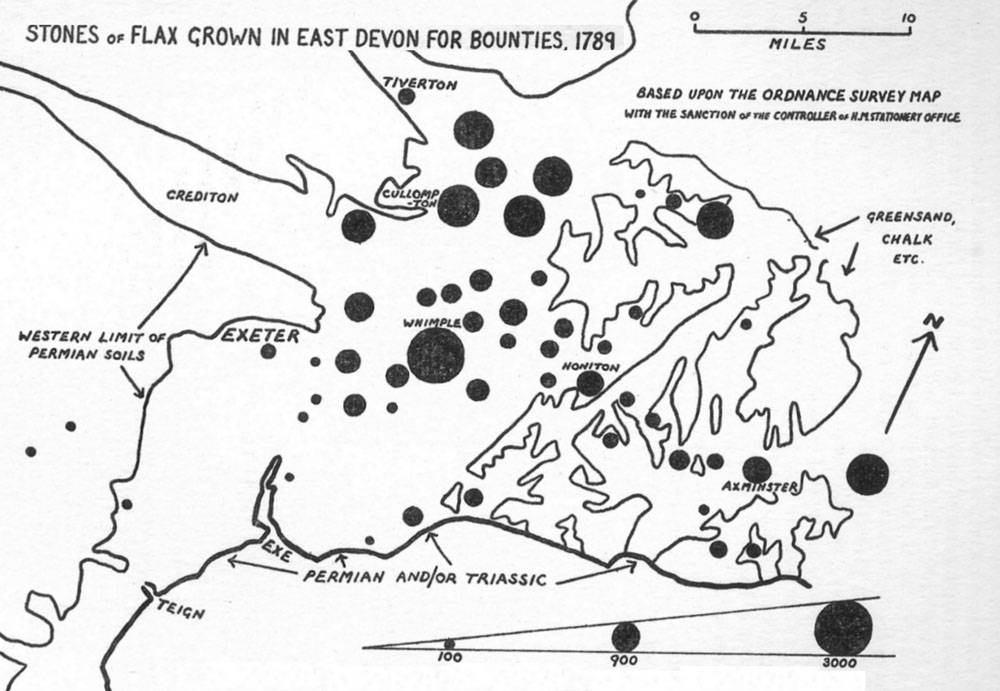

In the 18th century flax was relatively widely grown in East Devon for its fibre, and we know that late in the century some flax was still being grown around Axminster. Evidence for this comes from the ‘Hemp and flax bounty papers’ from 1785 to 1790, a transcript of which with relevance to Axminster is accessible on-line via the Axminster page of the genuki.org.uk website. The full set of bounty papers were used to create the map below for 1789, which comes from an article by Alfred H Shorter in ‘Devon & Cornwall Notes & Queries’, (Vol.XXIV Part II, April 1950). This article contains some further general information on flax growing in East Devon at that time.

Furthermore, the (admittedly recent, albeit historically-based) use of the name ‘Flax Meadow Lane’ in Axminster, and the survival locally of the surname Retter (from ‘retting’), both bear testament to the former importance of this crop.

Furthermore, the (admittedly recent, albeit historically-based) use of the name ‘Flax Meadow Lane’ in Axminster, and the survival locally of the surname Retter (from ‘retting’), both bear testament to the former importance of this crop.

However, we also know that by 1808, when Charles Vancouver (whose report is cited above in the context of butter production) carried out his review of agriculture in Devon, the cultivation of flax was in general decline, and nothing like as extensive or rewarding in the Axe valley as it was in South Somerset, or on the red soils around Whimple and Cullompton. Vancouver also noted how flax grown on the red soils west of Honiton had a pink colour which no amount of bleaching could remove.

Like butter, flax was generally produced on a contract basis, with the farmer preparing the ground and receiving a rental payment of between £3 and £6 per acre from a specialist grower who had a relationship with a merchant-processor. The grower would supply the seed and agree to have the crop harvested by a set date, usually in late October. Vancouver evidently found it hard to get a clear picture of exactly how the processing was organised.

Despite the decline in local cultivation, Pigot’s 1830 Directory shows that at that time the Town Mill at Axminster still included a flax spinner. It is also understood that there was at one time a rope factory above Dalwood, on the Corry, no doubt using flax as its raw material.

Information on the growing and processing of flax can be found on-line (e.g. on wildfibres.co.uk) and several local museums including Bridport and Crewkerne hold a lot of information about flax growing and processing in their areas.

Cider

We know from a letter written by Daniel Defoe in the 1720s (which can be read via the visionofbritain.org.uk website under ‘travel writing’: see his Letter 4, Part 1) that East Devon, from Topsham to Axminster, used at that time to send between 10,000 and 20,000 hogsheads of cider a year to London. A hogshead was not an entirely standard measure of volume, but was often used to refer to a barrel holding 50 gallons (making the range cited above between half a million and one million gallons). This may well have represented the high water mark of cider production in Devon, and all subsequent commentators refer to cider production as being in decline compared to former times.

Some 30 years later the rector of Axminster, John Pester, noted the existence of “… many orchards throughout the Parish, chiefly planted with such apple trees as make good cyder, rather sweet yet rough”.

Then by the early 1800s Charles Vancouver (whose 1808 report is referred to above in the context of both dairying and flax growing) observed that the orchards of East Devon were no longer as productive as before, and that “… from the frequency of planting young trees where the old ones have failed, a barrenness in many of the orchards has ensued. It is usual in the marly parts of this country to appropriate for orchards the large excavations formerly made in digging marl: here the apple trees are protected from most winds, and continue to flourish and bear longer than in less secure situations; but here again the fruit is more exposed in the spring and early part of summer to the frosts that occur at that season, than it possibly could be in higher situations”.

“The crop of apples generally through the valley of the Otter is very good, although it certainly does not produce a liquor equally rich as that grown upon stiffer land. Upon the high plains of Dunkerswell and Church Staunton, no material deficiency was noticed or heard of in point of quantity; and the quality of the cider is there contended to be equal to that of the South Hams, and much superior to the produce of the apple orchards in the sandy district below.”

He considered that the way that apple trees were managed, and cider made, was similar to the rest of Devon. “The great uncertainty of these crops, renders it a matter of much difficulty to state anything like an average produce through the county. The mean however, of several statements given in upon a period [of] seven years, varying from two and a half to five hogsheads per acre, will equal that of three hogsheads and two-fifths per acre through the county …” (equivalent to 1,360 pints of cider per acre). He reported that the average price of cider sold at the farm gate was 50s per hogshead (i.e. 1s per gallon). He also commented in passing that he had found no evidence of mistletoe in Devon cider orchards.

In 1838, when the tithe apportionment process was carried out, about 3% of the titheable land in Axminster parish was accounted for by orchards, a few as large as 5 acres, but most around an acre and a quarter.

In 1850 White’s directory described cider orchards as “… another source of income to the Devonshire farmer, the value of which has decreased nearly a half within the last twenty years”. Cider was also an important part of the ‘benefits in kind’ provided by farmers to their farm labourers, and to the casual workers who helped at busy times such as haymaking and harvest.

It was not until relatively late in the day that commercial cider making got going. The only very local commercial cider-makers for whom records have been found so far are Thomas Stone, who by 1906 was described as a cider manufacturer, as well as a wine and spirits merchant in Axminster, and Henry Coles of Fordwater Farm, All Saints (just north of Axminster), who made cider commercially during the 1920s and 1930s.

Axminster livestock auction market

Axminster has had a formal charter allowing markets to be held since the 13th century, and animals were sold as part of that. However it was not until the 19th century that clear evidence for the existence of organised livestock auctions can be found. By that time the Knight family held first a share in, and then, after 1871, all of, the manorial rights, including those pertaining to the market. Prior to the emergence of auctions the assumption is that animals were brought into the town on market day when they were considered to be ready to slaughter, and then sold by private agreement to one of the various butchers of the town.

For centuries the market was held in Market Square, and there were also temporary butchers shops (or ‘shambles’) there where the animals were killed and butchered, and their meat sold to householders.

At some point after Trinity Square was created, following the town-centre fire of 1834, the sale of livestock by public auction either moved there or was established there as a new way of selling animals. One of the prime movers in this process was Benjamin Gage, a local auctioneer, who advertised monthly sales in Trinity Square from 1857, according to ‘The Book of Axminster with Kilmington’ (which is the source for several of the facts quoted here).

Benjamin Gage was subsequently joined in partnership by his son John under the name B&J Gage. He was not the first auctioneer in Axminster, but he is the first who appears to have specialised in livestock. At very much the same time specialist cattle dealers were becoming established in the town, no doubt attracted by the regular auctions.

By the early years of the 20th century there was pressure on grounds of both public safety and public health for livestock markets to be held in dedicated premises, and for butchers to establish shops rather than using temporary stalls. In 1910 B&J Gage obtained a licence from the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, and on 11 May 1911 signed a conveyance with both the Knight family (as owners of the market rights) and Messrs R&C Snell (as fellow auctioneers and incoming purchasers from the Knights of the remaining Manorial rights, which were connected to the market). This conveyance coincided with the move of the weekly livestock auctions to a new location on Combe Fields, off South Street.

The site itself, which had been the garden of a large house, was bought by the Gages and the Snells, and work soon started on the construction of permanent buildings and livestock pens on a half-acre concrete base (to facilitate cleaning). It was opened on 6 October 1912, with space for 400 mature cattle, 300 calves, 2,000 sheep and 500 pigs and facilities for poultry and rabbits. The main auction ring was used for selling mature cattle, with most other animals being sold in their pens. The two firms of auctioneers, still competing head-to-head at that time, conducted their sales at opposite ends of the market.

By 1915, however, both Benjamin and John Gage had died, with the son pre-deceasing his father. Ellen Selina Gage, John’s widow, signed a further agreement regarding the market house, market toll rights and dues on 23 July 1914, the other parties to that agreement being Robert Snell (of R&C Snell), Henry Knight (senior and junior) and Axminster Rural District Council.

Copies of all of these agreements are held in the National Archives, and reference details can be found via their on-line ‘Discoveries’ catalogue.

Major Henry Knight (1849 to 1917), the older of the two Knight family signatories, had by 1911 moved away from Axminster to join the Army, and his only child, also called Henry (1878 to 1947), was by then a barrister in London. By 1915 they had sold off most if not all of their remaining land and property in Axminster, and in 1916 the formal title of Lord of the Manor was sold to Charles Snell (of R&C Snell). In later years one of the main auctioneers in Axminster was Arthur Benjamin Gage, the son of John Gage, who had joined Messrs R&C Snell following the effective merger of their two family firms.

All of the persons mentioned above are covered in the ‘pen portraits’ section of this website.

In the 1950s the manorial and market rights were bought by Frank Rowe of Messrs R&C Snell, and have subsequently passed to Jim Rowe, the present Lord of the Manor of Axminster. Messrs R&C Snell have been absorbed into Symonds & Sampson. In the 1980s and 1990s Graham Barton of R&C Snell won several titles in the UK National Auction Competitions.

The market was at its most active in the years between the 1920s and the 1980s, but with the rise in large slaughterhouses and national butchery chains the auction as a sales mechanism declined in importance, and at very much the same time the country suffered a series of animal disease catastrophes. In the late 1980s BSE (more widely known as ‘mad cow disease’) primarily revealed itself in dairy cattle, though the disruption to markets caused by animal movement controls also affected beef and sheep farmers. Then there was the widespread foot-and-mouth outbreak of 2001, which directly affected all types of livestock, including farms in East Devon. The rigours of movement controls and traceability were probably the final nail in the coffin for Axminster’s livestock market, and the site was sold for re-development as housing in 2006.